To those unfamiliar with the concept of Classical and Operant Conditioning, let’s break it down to history and how it affects us in everyday situations.

The idea, like most, has been around for some time, but it gained notice from when Edwin Burket Twitmyer and his study on the Patellar Tendon (part of your knee) and its reflex when hit. I know what you are thinking. Shouldn’t I be covering Pavlov? Technically, yes, but Twitmyer was the first to actually note Classical and Operant conditioning in humans, and publish his findings earlier than Pavlov. In his version, he would warn patients that he would ring a bell, then a device would hit the person’s knee. He accidentally rang the bell during one of his patient’s trials, and out of serendipity, the subject, who wasn’t hit in the knee, actually showed a reflex. It was then concluded, after many trials, that given with an auditory stimulus can trigger a conditioned reflexive response [1]. Sadly, Twitmyer’s work was not given much credit, because Pavlov kinda stole his thunder… with puppies.

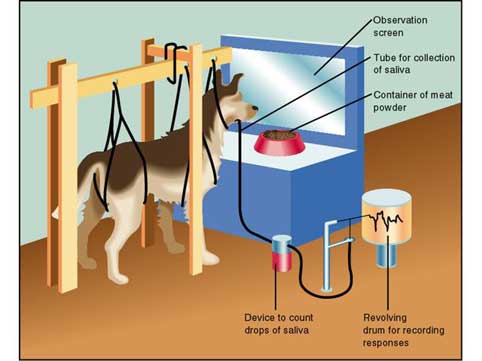

Ivan Pavlov (1849-1936) was a Russian Physiologist that took Twitmeyer’s credit in Classical Conditioning. To be fair, Pavlov also contributed to medicine when he studied the digestive systems of dogs, which led to him winning the Nobel Peace Prize in 1904. Nevertheless, both men have contributed to many learning theories and psychology. But back on topic, the idea was discovered accidentallty, and Pavlov noticed when his lab assistant would come and feed the dogs, the dogs would salivate. This led him to test the idea. In behaviorist terms, food and salivation are unconditioned stimuli and responses. Now, when the noted lab assistant would appear, the dogs salivated at the sight, So, Pavlov decided to try devices like metronomes and bells, and see if the dogs would react. Now, right away, it didn’t work, but when he paired it with the food, the dogs begin to learn that the associated stimulus (or neutral stimulus) would be paired with them being fed. Over time, the dog now associates the stimulus with the idea it will get food. This is called the operant conditioning. Here is the steps to understand.

- Food (Unconditioned Stimuli) —> Salivation (Unconditioned Response)

- A bell ringing (neutral stimulus) —> No response.

- Pair bell with food (neutral and unconditioned stimuli) —> Salivation (Response)

- Ringing the bell (Conditioned Stimuli) —> Salivation (Unconditioned Response

The illustration below showed how Pavlov did his experiments.

Operant Conditioning is a bit different. While classical revolves around reflexive behavior, operant is a bit more instrumental. Operant Conditioning is where organisms learn (a) the strength of a behavior is modified by the behavior’s consequences, such as reward or punishment, and (b) the behavior is controlled by antecedents called “discriminative stimuli” which come to signal those consequences. This was mainly promoted by B.F. Skinner (1904-1990) in the 1940s. He created what is known as the Operant Conditioning Chamber, and it involves with organisms, mainly rats, to learn what consequences will happen. In this case, when working with rats, he would have two levers. One to rig a shock, while the other to rig with dispensing food. What happened next? Well, he would associate the levers with lights or colors, and if the rats would select the wrong one, they get shocked. If they chose right, then they get food.

We use these everyday when learning things, whether it would be a parent calling dinner for the kids, or spanking a child as punishment for breaking a rule. Granted, there will be varying factors, but nevertheless, Pavlov, Twitmyer, and Skinner helped us understand how we learn.

Noted Works:

Irwin, F. W. (1943). Edwin Burket Twitmyer: 1873-1943. The American Journal of Psychology, 56, 451-453.

Hothersall, D. (2004). History of Psychology. McGraw-Hill.